Regina Spektor's Answer Song to John Keats

How "All the Rowboats" works with "Ode on a Grecian Urn" to create a timeless , essential tension. And why we need a little tension in our lives.

I’m lucky enough to have several “cool stories” to trot out from time to time. One of my favorites is that I knew Regina Spektor before she was famous. Ok ok, I didn’t actually “know” her; we never exchanged more than a nodding “hello” or “excuse me,” but I was there at the beginning.

Back in the late 90’s I lived in New York City and one of my favorite things to do was go down to Alphabet City on Monday nights for the open-mic weirdness of my beloved Sidewalk Café on Avenue A. The Sidewalk was the epicenter of a quirky and exhilarating artistic movement. A musician named Lach had invented a scene that came to be known as “Anti-folk” and the Sidewalk was its home base in 1998. It was weird, exciting, and glorious and I was there, sitting in the back ever so shyly, week after week, taking in all the beautiful art this community produced. To this day it still basically defines my ideal artistic community.

Back in those days, Regina Spektor was just starting out and she quickly made herself a star at the Sidewalk Café Anti-folk hootenanny. The captivating, shockingly original artist we know today was already almost fully formed right from the beginning. All of the artists who performed on that stage would have stood out in almost any crowd. Spektor stood miles above even this illustrious group of individualists.

Each time I saw her, she would meekly, almost apologetically, approach the beaten-up, adequately-tuned piano on the Sidewalk’s cramped stage. She would sit, grin, and, with a humility almost painful to watch, say hello to the crowd with a quiet voice before introducing her songs.

Then a magical transformation would take place as Regina Spektor possessed the body and soul of this meek young woman. Even then, before the record deals and critical success, her performance looked mostly like what the world beyond the Sidewalk would eventually see once the great artist blossomed into her full potential. Take this performance of “All the Rowboats” for example:

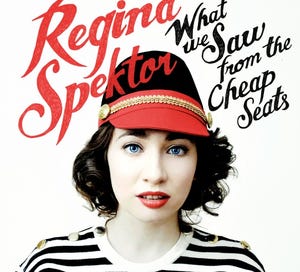

I’d like to spend the rest of my time here focusing on that song, “All the Rowboats,” which was released on her seminal album from 2012, What We Saw From the Cheap Seats. I use the term seminal because it remains one of my personal favorite records, but it was positively reviewed by experts too, if that matters.

“Rowboats” has always stood out to me on this record of uniformly excellent songs. Purely on the level of sound, I’m fascinated by how the song balances beauty and anxiety. Spektor’s clear and angelic voice leads the enchanting melody of the song, guided by her expert piano-playing. There something gorgeous about the song. And yet that beauty is driven forward by a pulsating rhythm that is almost John Carpenteresque. If Spektor were not singing, the song would serve nicely as the soundtrack to a hypothetical David Gordon Green reboot of Prince of Darkness. This song’s ability to work in both registers is amazing.

That balancing act, holding beauty and anxiety neatly together, isn’t just musically interesting, however. It’s intimately connected to the lyrics and the song’s “point.”

The song’s lyrics are filled with images from an art museum. Stunning works of art are tortured for being beautiful. Spektor makes us re-interpret the museum as a mausoleum. The artworks have been incarcerated for being beautiful and are condemned to serve “maximum sentences.” What we the museum patrons have always admired is the agony of a living thing frozen in amber. “All the rowboats in the oil paintings, they keep trying to row away,” is the song’s refrain.

As with any great work of art, it’s impossible to settle on a single “correct reading” of “All the Rowboats.” One might understand it metaphorically as the lament of a beautiful and talented woman feeling captured by her gifts, objectified, and put on display for an adoring audience who can never really be more than consumers.

There’s also the possibility that the song can be understood as a statement against how elite cultural institutions sanctify some works of art and create exclusive shrines for them that effectively cut them off from the populace, reserving them for a rarefied, privileged few. Walter Benjamin’s “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction,” would be a good text to review in service of such a reading.

Without dismissing either of those approaches to the song, I’d like to instead appreciate it for how it courageously “talks back” to John Keats. In particular, I’ve always thought of the song as a kind of “answer song” recorded in response to “Ode on a Grecian Urn.”

The answer song is an under-appreciated genre in music and many of my favorite country songs are answer songs. Kitty Wells’ immortal song “It Wasn’t God Who Made Honkey Tonk Angels,” is the prototypical answer song. Its very existence is as a sharp, instant retort to Hank Thomson’s “The Wild Side of Life,” which rather misogynistically blamed loose women for the moral failings of men.

“All the Rowboats” is in many ways a direct response to some of the premises of Keats’ great poem (please do not understand this to be a dismissal of Keats — I love him and “Grecian Urn.” I will say more about this at the end).

The poem is one of English-language literature’s immense warhorses so there have been countless analyses and evaluations of “Ode on a Grecian Urn.” The Wikipedia entry I linked to above should get you started. One basic understanding of the poem, however, is that the Grecian Urn has preserved images of beauty for all time, as a kind of offering and comfort to the ages. The last stanza has often been read as evidence for this reading:

When old age shall this generation waste,

Thou shalt remain, in midst of other woe

Than ours, a friend to man, to whom thou say'st,

"Beauty is truth, truth beauty,"—that is all

Ye know on earth, and all ye need to know. (lines 46–50)

The idea behind this understanding of the poem is that the urn captures the glorious torrents of life and preserves them in their undiminished state. The stanza about two lovers on the cusp of ecstasy is a good example:

Bold Lover, never, never canst thou kiss,

Though winning near the goal—yet, do not grieve;

She cannot fade, though thou hast not thy bliss,

For ever wilt thou love, and she be fair! (lines 17–20)

Here Keats puts a positive spin on sexual frustration. He leaves only the anticipation of fulfillment and excludes the disappointments that come with the ravages of time.

One reason I think about this poem when listening to “All the Rowboats,” has to do with the poetic technique of ekphrasis, a word we use for poems that describe visual art. That is exactly what “Grecian Urn” is, after all: Keats is describing a work of visual art.

There are levels of representation here, however. Keats’ urn, the object being described, also depicts music:

Heard melodies are sweet, but those unheard

Are sweeter; therefore, ye soft pipes, play on;

Not to the sensual ear, but, more endear'd,

Pipe to the spirit ditties of no tone: (lines 11–14)

Michael Clune explores how artists try to overcome the passage of time in his 2013 book Writing Against Time. He devotes a chapter to what he calls “Imaginary Music” and, unsurprisingly, focuses quite a bit on Keats. He writes, “The poem attributes to a visual image of music powers that the ineluctably temporal form of heard music lacks. The poem’s particular mode of visuality does not represent a simple surrender to statis, but a method for fusing movement and stillness” (43). In essence, Clune is interested in the ways that Keats tries to make something as fleeting and ephemeral as unrecorded music into something permanent and outside the powers of time’s passage.

This takes me back to Spektor’s song as a kind of answer to Keats from the genre of music itself. “All the Rowboats” also makes use of ekphrasis; it represents paintings in verse. And it comes to an entirely different conclusion about the act of preservation.

Gone are all of Keats’ romantic gestures toward immortality. The corollaries of the urn’s sweet, unheard melodies are nightmarish in Spektor’s reading of the situation:

“And the captains’

worried faces

stay contorted and

starin’ at the waves”

Spektor even has a direct response to Keats’ idealistic musical representation:

“God, I pity the violins

in glass coffins, they

keep coughin’

They’ve forgotten,

forgotten how to sing,

how to sing”

The song refutes Keats literally note for note. This does not diminish Keats for me, however. It only enriches his poem.

Life is Tension (In Which I Do a Bit of Philosophy)

I am a big advocate of tension. I believe that virtually everything we experience exists in an essential tension with something else. Most of the mistakes we make, politically and in matters of taste, happen — I believe, at least — because we don’t acknowledge the vitality of the tensions we encounter. Instead, we choose a side and dig our heels into the defense of that position — our side good, the other side bad. This happens in art as much as anything else these days. If one has committed to the MCU then one must seek out and destroy the Zack Snyder fans out there.

In this environment, it is tempting to say that Regina Spektor has corrected a “huge problem” in Keats. The more committed ideologues will then conclude that “Keats is actually very bad,” or “Keats is trash.”

I can’t believe that Spektor herself would say such a thing. To me, this is an example of a great artist identifying an interesting problem to solve in another great artist, a beautiful conversation to take part in.

Her rejoinder does not call for the disposal of “Grecian Urn;” it makes the poem all the more vital. It has created a useful tension, like an electron finding a proton to circle a nucleus with. Together they actually form the atom and one is less meaningful without the other.

Spektor, in her answer song to Keats provides the other end of a tension that makes both works timeless. Life is tension, tension is life. That is all we know on Earth — and all we need to know.

Splendid reflection, Danny. Yes, both/and is the green fields of artist and mystic; either/or the prison yard of bear-pit algorithms