Upon entering the hallowed halls of academia, I noticed two distinct cultural styles.

One felt distinctly “corporate America.” Everything had to be hashed-out, ideated, and operationalized. Professionalism as moral duty, that sort of thing. These folks dressed and spoke as if HR was following them around with an open Excel spreadsheet.

There was another type. This group rode the pendulum to the other extreme, like Miley Cyrus on a wrecking ball. It wasn't that they dressed poorly; few people dress as carelessly as me. It was a more general posture of cool aloofness. Smoke breaks, elaborate profanity, a desperation to say smart things about contemporary pop culture hot topics.

Most people didn't fall entirely into either of these cultures; reality is never as tidy as our stereotypes. But the stereotypes exist for a reason, and if you look at PhD-granting institutions long enough, patterns will emerge.

English departments are famously fractious and our fault lines tend to encourage competing cultural styles. Your Rhet/Comp folks lean toward the corporate-professionalism end of the spectrum and will absolutely assess your asses. The High Theory faction of Cultural Studies, on the other hand, will snort and eyeroll if Faulkner is mentioned and prefer to swear a lot about Succession and The Wire

Alas, the Horseshoe Theory Holds True Again

It always seemed to me that these two subcultures are really not so different. They are in fact siblings, estranged, but bound together. They've chosen different means of expressing it, but each cultural style seeks the same goal: "don’t become the cliché of the archaic, tweedy College Professor."

A common denominator between these rivals is the desperate desire to be "relevant."

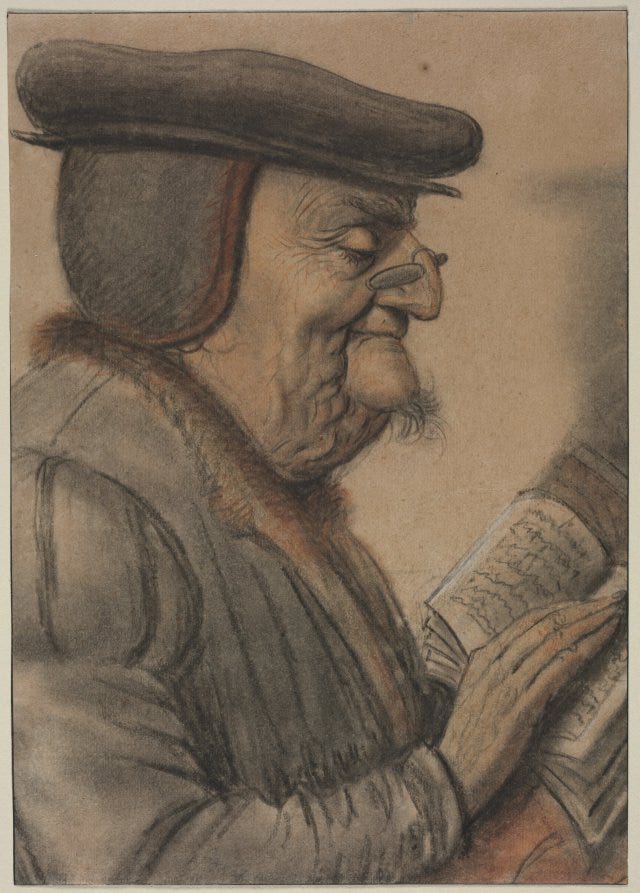

And what could be less relevant than an egghead thinking thoughts about moldy books from the past? Especially if the text or author can’t readily be jammed into the discourse of current professional fashions.

It seems to me this particular professional anxiety is tethered to a more general fear of being perceived as old or ideologically backward, which is a common trait among the literati. It's the same reason some humanities academics are often so loathe to criticize emerging technologies. Five years ago, if you'd presented a paper questioning the impact of cell phones and social media on student attention spans, a predictable response would have been something droll, like "you DO know that the book is a technology too, right?"

What’s behind these reflexive responses is fear: the fear of being associated with Jonathan Haidt or whomever. Anything, anything at all, to not be lined up against a wall with the olds.

The Seductive Lure of “Being Relevant”

Surely, in Literary Studies one can understand the desperation to seem relevant. In a higher ed landscape where ROI is the overwhelming force, the humanities are under heavy pressure to demonstrate value. And this is not even a new phenomenon.

For many decades, at least back to the rise of the "New Critics" in the middle Twentieth Century, literary studies has tried to tail the sciences, presenting itself as, if not quite scientific, at least professionally rigorous and respectable. The famous "Leavis/Snow" debates are a good example of this phenomenon.

Post-1968, the pressure to assert professional relevance diverged, like the road in Frost's poem, into two paths, which I've caricatured here. One group mimics an ideal vision of corporate citizenry. The other seeks to win the affections of an imagined youth, waging a righteous war of rejecting wicked, authoritarian “tradition.”

Both run away from the image of the disinterested academic, for whom the pursuit of knowledge, wisdom, and the Good is the only proper end of education (this too is a kind of fantasy, I realize, but still an ideal worth keeping in the foreground of our imagination).

But if we look at reality as it actually exists, it's clear that these approaches have done nothing to save the academic study of literature from the perception of irrelevance.

Take a moment and look at the numerical decline of English majors. And History. And Philosophy. And who even still remembers that there used to be Classics majors running around college campuses? These departments are shuttering in astonishing numbers. One wonders if irrelevance is in fact encoded in the very DNA of the humanities.

The Way Forward

I have an unpopular opinion about all this.

If there is a future for literary study, it rests in the vocation's irrelevance, not its utility. Its timelessness, not its timeliness.

A metaphor. The well-intended desire to hitch literature and writing to immediate and contemporary fashions and ideologies has an equivalent: evangelical churches convincing themselves that fog machines and bass guitars will make Christianity cool enough that the kids will give up dance and travel sports and come to church instead. I understand the thinking, but in the end, it's just sad.

Similarly, there’s nothing English professors can do to make people flock back to the Old Religion of the Life of the Mind in the age of TikTok. Like a withering little church we can really only be there for when someone eventually decides they need us. It might happen. The pace of modernity will certainly start burning people out and they’ll seek something; something that transcends the present. Perhaps even something quieter and slower, like literature. They won’t come in great numbers, but someone will eventually come.

For too long, the humanities have safely huddled inside academic institutions. Now those institutions are not so safe, and people wonder what might happen. The state of higher ed can seem like a death blow to Culture, I know.

It very well may be that literature will have to survive outside the academy. If that is the case, so be it. That may in fact be preferable.

How much damage have we done to literature by contorting it to fit contemporary ideological molds? Certainly old books and old movies still have something to say to modern people, but often it isn't what we want to hear. That's the art and thinking that get ground up in our professional machinery.

I have no idea what the future of the humanities looks like outside the economic and professional structures of institutional academia. Will it look ancient and monastic? Will it be an explosion of private literary societies? Will it look like something we can’t imagine yet?

But it seems to me that the humanities will survive, because there are still people who love them, whether it is professionally advantageous or not.

What to do in this moment of transition between two worlds?

Those of us who care, should start saving the journals and books that academic libraries are tossing in the wake of ubiquitous digital access. Pull them from the dumpsters. Put the bound paper on shelves. My own department did exactly this, and we have continued to fill the empty offices in our wing with the material objects of Culture. Organize communities around these archives. See what develops. When the power goes out, come see us.

Read your way through your collections. Seek out others with archives of their own. Write about your experiences in the archives. Publish them on your Substacks or print your own zines that you put into the hands of others.

When the universities close, the archives can still persist, and our irrelevance to crumbling institutions might be what ultimately saves the humanities for whomever comes after us. Which is really the point.

Storing fragments against the ruins. Nice work, Danny!

As a history nerd, this is exactly how I feel. I continue on my journey through academia, in spite of hearing that this isn’t of value, isn’t a commodity, isn’t a real pursuit. It’s a real pursuit because I am, in fact, pursuing it. Humanities are overlooked, downplayed, or (at worst) ignored. I’m happy to contribute in a small room of people who share my passion, who see the world the way that I do. Amazing read! Thank you so much.